When Hurricane Helene struck North Carolina in 2024, helicopters pierced storm clouds, lifting stranded residents to safety. The uniformed rescuers weren't distant federal troops but familiar faces: teachers, electricians, and nurses who had traded civilian clothes for fatigues. Neighbors helping neighbors, in the most literal sense.

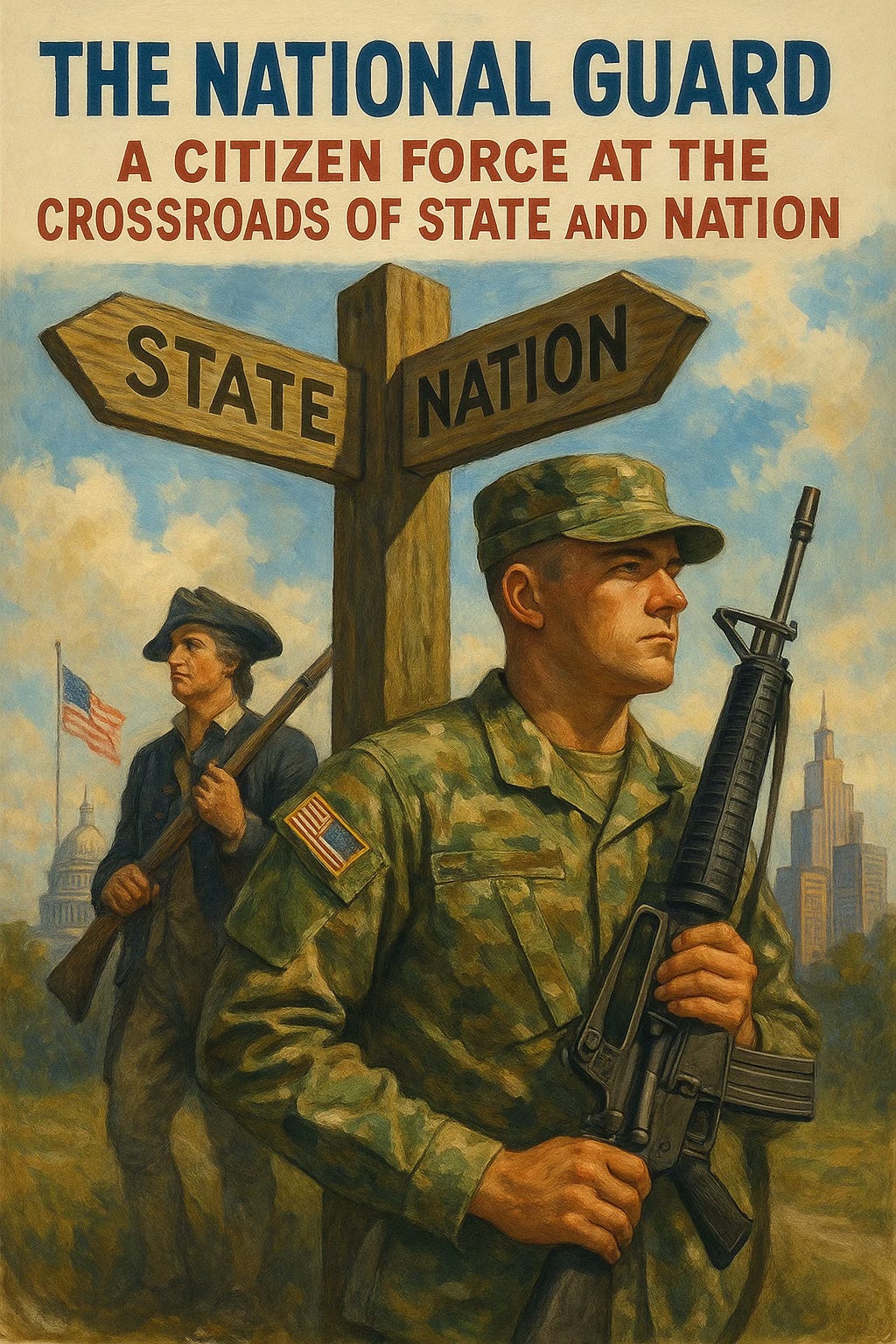

This response captures what makes the National Guard singular among American military institutions: a force of citizen-soldiers that bridges the local and the national, the ordinary and the extraordinary. With roughly 325,000 members spread across all 50 states and territories, the Guard occupies a space no other force does. Its troops live among us. They serve governors first, the President second. They hold dual allegiances to their communities and to their country.

Yet for all its visibility in times of crisis, the Guard remains poorly understood. What exactly is it? Who commands it, and when? What can it do, and what can't it?

Deep Roots, Split Loyalties

The Guard's story begins with colonial militias—citizen-soldiers who could drop their tools and take up arms when needed. The modern National Guard took shape with the Militia Act of 1903, which formally integrated state militias into the federal military framework. The result was a dual-role system still in place today: one foot in the statehouse, the other in the Pentagon.

The Two-Boss System

The National Guard's defining feature, its constitutional split-screen, is its chain of command. Unlike any other branch of the military, a single Guard unit can report to either a state governor or the President of the United States, depending on how it is activated.

When under state authority, the Guard acts as an arm of the governor: missions are coordinated locally, troops can support police in crises, and although the funding and equipment come from Washington, the orders do not.

When federalized, the Guard becomes part of the U.S. military machine. The President gives the orders, the Pentagon runs the operation, and law enforcement powers vanish. Troops can be sent abroad or anywhere in the country, but they cannot arrest civilians or patrol city streets.

This dual structure offers flexibility in times of crisis, but it also opens the door to conflict, especially when governors and presidents do not see eye to eye.

What It Can and Cannot Do

Under state control, Guard units can assist police during civil unrest, respond to natural disasters, and help manage public health emergencies. They are, in essence, a domestic backup force: armed, trained, and legally allowed to act in support of civilian authorities.

Under federal control, that all changes. Once federalized, the Guard becomes a traditional military entity subject to the Posse Comitatus Act, a post-Reconstruction statute rooted in a simple democratic premise: federal troops do not police the American people.

These distinctions matter. In recent years, disputes over border deployments and responses to civil unrest have turned the Guard's dual role into a political tug-of-war.

The Citizen-Soldier Model

What sets the National Guard apart is not just its dual command or flexible missions; it is the people who serve. These are not full-time soldiers stationed on faraway bases. They are schoolteachers, nurses, electricians, and small business owners. Their boots are laced on weekends; on weekdays, they coach soccer and serve on PTA boards.

When disaster strikes, they show up not only with military training but with a map of back roads in their heads and the mayor’s number in their phones. That blend of expertise and local knowledge makes them especially effective in emergencies.

But the citizen-soldier ideal is under strain. Today’s Guardsmen deploy more often and for longer stretches—domestically to floods and fires, internationally to war zones, then back again in time for wildfire season. Climate change has made natural disasters more frequent and severe, and America's global military commitments remain relentless.

The system runs on goodwill: from families, from employers, from the communities the Guard is meant to protect. But as deployments mount and the rhythm becomes unsustainable, that quiet social contract begins to fray.

A Force Transformed

In the 21st century, the National Guard's workload has ballooned. Domestic disaster deployments now occur at triple the rate they did in the 1990s, and overseas missions have surged since 9/11. Today's citizen-soldiers do not just fight fires and sandbag rivers; they run cyber-defense operations and administer vaccines during pandemics. The COVID-19 response showcased the Guard’s versatility, but also its limits.

These expanded roles are reshaping the very idea of a part-time force. What began as a local militia has become a jack-of-all-trades responder in an age of compound crises.

The Bottom Line

And yet, the Guard endures because of its proximity, its credibility, and its people. It works because it is rooted in neighborhoods, not installations. But that foundation is no longer guaranteed. As deployments accelerate and expectations mount, the fragile balance of civilian life and military service begins to tip.

When leaders argue over Guard deployments, they are not just sparring over policy. They are confronting a deeper question: Can a nation sustain a military force that belongs both to the Pentagon and to the parish hall? One that protects the homeland not just from foreign enemies but from floods, fires, and fractures within?

The answer matters. In an era of rising threats and diminishing trust, we need institutions that can straddle the line between the local and the national. For nearly four centuries, the Guard has done just that. Whether it continues to do so will determine if America can keep its most essential promise: that in our darkest hours, help will come from next door.